From BAML to UBS: how 15 banks stack up on ‘last look’

Disclosures show striking differences on pre-hedging, hold times and trade acceptance

Need to know

- Foreign exchange dealers have been changing their practices and updating their disclosures since the publication last year of a new code of conduct for the market.

- Risk.net has compiled disclosures for 15 large banks. The disclosures vary in detail, and dealing practices can be strikingly different.

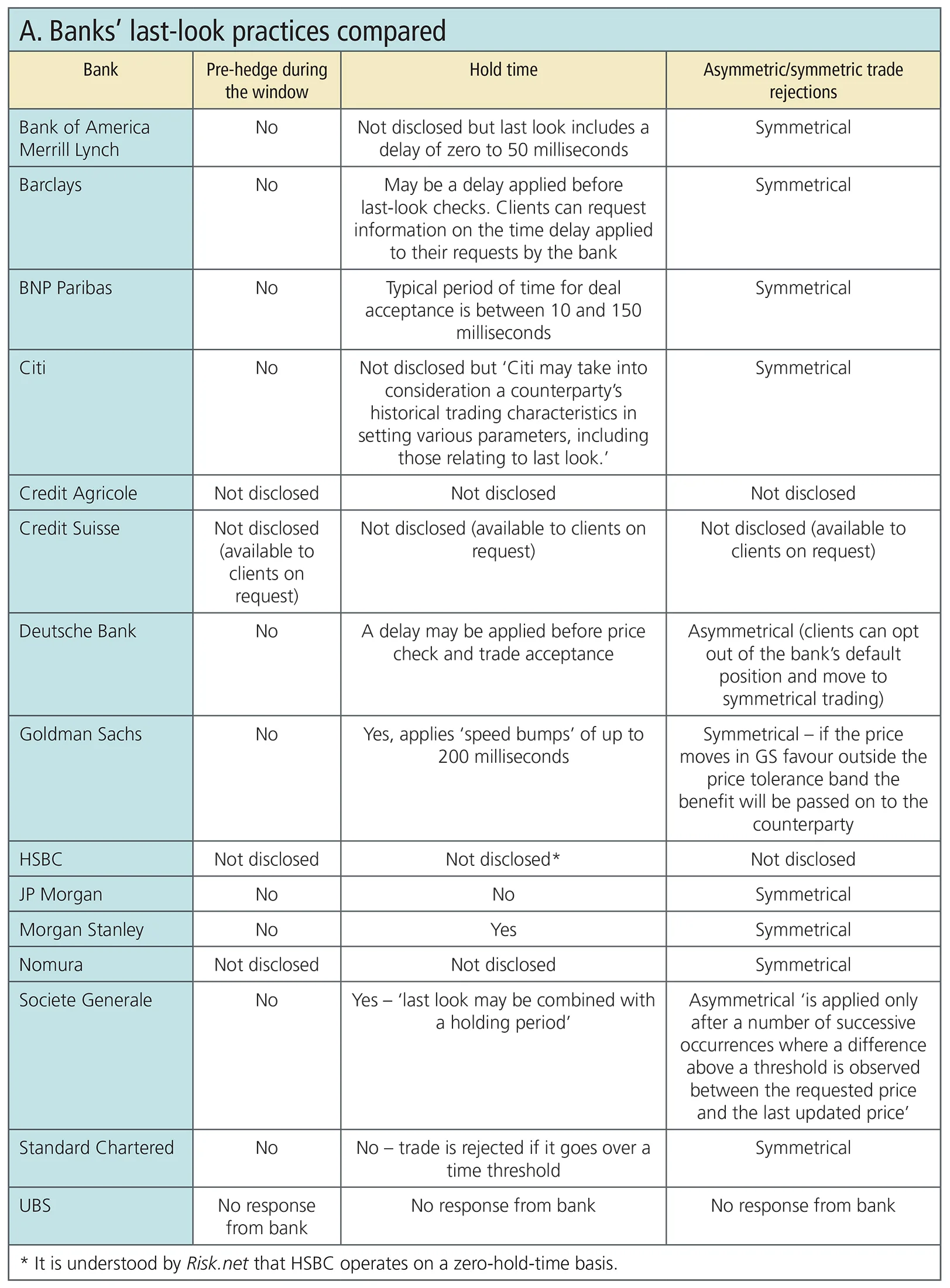

- The resulting table compares policies on three topics that can be controversial: pre-hedging, additional hold times, and the treatment of price moves prior to trade acceptance.

- “It’s a buyer-beware situation. The notion is ‘You’ve seen our terms of business and how we operate. So, you decide whether you want to trade with us’,” says one senior forex trader.

- The time-lag between receipt of a trade request and its acceptance can vary: BNP Paribas says trades are typically accepted within 10–150 milliseconds; Goldman Sachs may add a 200-millisecond ‘speed bump’ to some trades.

- If the price moves during this period, banks have a wide variety of policies – in most cases, the trade will be rejected once the move crosses a threshold.

A newcomer to foreign exchange might assume the story of a trade ends at the point a client decides to accept a dealer’s price: both parties want to trade and a rate has been agreed, so surely that’s the end of it, right?

Wrong. What happens after that point depends on which dealer is involved. The order could be accepted almost instantly, rejected by the dealer, or deliberately held up for as much as 200 milliseconds prior to acceptance. Some dealers may hedge the trade before it is accepted, locking in their profit.

If the market moves during this period – because it has been pre-hedged or for any other reason – then the outcome again depends on the dealer. Some take a symmetrical approach: above a certain threshold, the trade will be rejected whether the price has moved in favour of the dealer or the client. Other banks are asymmetrical, executing the trade if the price moves in their favour, and rejecting it if it moves in the client’s favour.

These practices are changing – and disclosure is improving – as a result of the forex market’s global code of conduct, first published in May last year. But big banks remain split. In this article, Risk.net has compiled the disclosures and compared them side by side, looking at pre-hedging, hold times, and the treatment of price movements (see table A).

“It’s the first time I’ve seen the policies laid out in this way. I think many people will be surprised there are such big differences between the banks,” says David Clark, chair of the European Venues and Intermediaries Association.

Paul Chappell, a member of the executive committee at ACI Financial Markets Association, says: “This precisely highlights some of the things the industry has been grappling with, as to whether we have a level playing field here. The attention-grabbing bit is the people who are not prepared to disclose what their policy is at the moment.”

Of the 15 banks, four make no disclosure regarding their use of pre-hedging, while six do not say whether they apply a hold time or other deliberate delay. In two cases, banks state they will share information if asked by a client.

A forex options trading head at one dealer argues the status quo allows customers to make up their own minds about which counterparties to use: “It’s a buyer-beware situation. The notion is ‘You’ve seen our terms of business and how we operate. So, you decide whether you want to trade with us’.”

A source at another dealer sees it differently, arguing it is not “customer friendly” to expect clients to read all of the disclosures: “How the hell is it not obvious in every category what everyone does? It just shouldn’t be the case.”

Fixing this might just be a matter of time – the code is still relatively new, and some say the industry will eventually end up more aligned. “As the code matures and people agree to converge with those practices, I would expect a move towards harmonisation. So, a year or two, or three, down the line, there will be less dispersion,” says Xavier Porterfield, head of research at New Change Currency Consultants.

It remains to be seen how much patience clients have.

In the meantime, many banks are refusing to say any more than they have already put in the public domain. Barclays, BNP Paribas, Citi, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Nomura and UBS all declined to comment for this article, or did not respond to requests for comment.

Checks and imbalances

The drafting of the code generated intense debate about some of these practices, under the broad heading of ‘last look’. Technically, the term refers to a final check by the dealer – of the client’s credit line, the details of the trade, and the current market price – which could result in the trade being rejected.

These checks might take 5 milliseconds, or 100 – during which period a dealer can see multiple price updates from trading platforms. Prices are refreshed every 5 milliseconds on EBS Matching, for example, and every 25 milliseconds on Reuters Matching.

Hold times can be applied separately, but not all banks use that term. In all, six banks state that some kind of delay can be applied to the trade in addition to the last-look window: Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Barclays, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Societe Generale. At Goldman, in some cases, a 200-millisecond ‘speed bump’ can be applied.

Others offer vague statements, or no disclosure on the practice. BNP Paribas says there can be a lag of between 10 milliseconds and 150 milliseconds between trade request and trade acceptance, but does not explain why. Only JP Morgan and Standard Chartered say they do not apply hold times.

“Last look can be two things. Instantaneously, once you’ve checked the order, do you accept or not? And then, secondly, there is what I would say is a porous class of behaviour, which is whether you hold the order for some additional period, before deciding to accept or reject. And that’s quite an important distinction,” says the forex options head.

It’s the first time I’ve seen the policies laid out in this way. I think many people will be surprised there are such big differences between the banks

David Clark, European Venues and Intermediaries Association.

It’s also a nuanced one. There isn’t much opposition to pre-trade checks in principle – the question is how long they should take, and whether a dealer should be allowed to do anything during the window, other than simply deciding to accept or reject. Adjusting prices that are being displayed to other clients could tip the market off to the pending trade; pre-hedging may seem sensible to a dealer, but viewed from the client’s perspective might also look like front-running. In both cases, there is the potential to move the market against the client.

Hold times give rise to similar tensions. Critics charge that if pre-trade checks are complete, the only reason to put a brake on the transaction is to give the dealer more time in which to observe market prices moving. This might increase the chance of a trade being rejected, or encourage pre-hedging – both bad things from the client’s point of view. But banks that use the practice justify it as a protection against so-called ‘toxic’ flows. These can take many forms – a high-frequency trader, for example, that only wants to trade when it can see the bank’s price is stale, or a client that sprays an order across the market, prompting multiple dealers to hedge simultaneously, which can make it difficult or impossible to capture profit on the trade.

The global forex code doesn’t bar last look or additional hold times, but encourages transparency, so clients understand how their liquidity provider behaves. In many cases, the resulting disclosures are the first time dealers have publicly laid out their policies on these issues.

One of the most detailed is from Goldman Sachs. In a document that appears to have been finalised on January 18, the bank says it applies hold periods of between zero and 100 milliseconds for a majority of counterparties, “with a hold period of 200 milliseconds applying to a limited number of counterparties,” according to the disclosure.

“The hold period that applies to a particular counterparty depends on which pre-defined ‘tier’ it is allocated to, with each tier representing a different hold period.”

A client’s tier is determined in part by “reviews of the counterparty’s trading history, including a review of the amount by which Goldman Sachs’ internal prices have moved for a short period of time following receipt of a counterparty’s electronic trading requests,” the document reveals.

Morgan Stanley also says it may apply a hold time for “some counterparties” in addition to last-look trade-acceptance parameters.

In both cases, the banks are framing hold times essentially as a means of protection – a way to deter the market’s speed demons, or to detect cases in which a client may have sprayed an order across multiple liquidity providers.

The smarter market-making algos are tailoring hold times to the profile of the client

Xavier Porterfield, New Change Currency Consultants

New Change’s Porterfield says this kind of client profiling is becoming increasingly common in cash forex: “The smarter market-making algos are tailoring hold times to the profile of the client. The client’s business is profiled, so the model is data mining the client’s trade with identifiers and, based on the profile, the hold window will be set to try and protect the dealer.”

Societe Generale also says it may apply a hold period, but doesn’t shed any light on the conditions that trigger it. During the last-look window, the bank says it monitors the “trade request price” – the rate originally quoted by the bank, which the client wants to take – and says it will reject the trade if it is too far from the most recent price shown in the market.

The disclosure adds that the last-look window “may be combined with a ‘holding period’, in which case SG will attempt to execute the trade request during a certain period of time and will reject the trade if the price difference is still above the threshold after the ‘holding period’.”

Whatever the rationale, a lag of 50 milliseconds – let alone 200 – is enough for the market to move a long way. On October 7, 2016, for example, when the British pound experienced a flash crash, the largest move in the sterling/US dollar market during a 50-millisecond period was 14 pips according to New Change Data; over 200 milliseconds, it moved 19 pips.

On the same day, the less-liquid South African rand/US dollar market witnessed a 2,764-pip move during a 200-millisecond period, equivalent to a 276-pip move in sterling/US dollar.

The question for banks that have longer last-look windows or additional hold times is what they do during this period.

The code urges firms to limit the use of client information – to pre-hedge the trade or to update their own prices – unless this is disclosed, but the details are complex. In the last-look window itself – a feature of electronic trading – the code says banks should not hedge, unless they are acting as an agent. At other times, pre-hedging is allowed as long as the bank is acting as principal and does so “fairly and with transparency”. Of the 15 banks, 10 state they do not pre-hedge, while five offer no disclosure or failed to respond to questions (see box: Pre-hedging: disclosures still patchy). In these cases, the disclosures relate specifically to hedging during the last-look window. Some banks, including BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and Societe Generale, state that they may pre-hedge trades requested via voice or email.

To remove some of the suspicions that hang over the trade acceptance period, some dealers have voluntarily moved to a hold time of zero, meaning they conduct last-look checks with no additional buffer.

“Once you have undertaken a credit check and done a pre-approval check of someone’s availability to do the trade, there is no justification for a hold time,” says ACI’s Chappell.

Non-bank liquidity provider XTX Markets moved to a zero-hold-time model in August last year, arguing no extra time was needed to complete checks prior to execution. JP Morgan adopted the change in 2016, and Risk.net understands other banks, including HSBC, have also moved to a zero hold time.

Symmetrical vs asymmetrical approaches

Hold times or not, any kind of delay creates a risk that the market price could move relative to the client’s order, making the order price better or worse for the client. The next question is how the dealer responds.

In the past, many banks are believed to have applied an asymmetrical policy, more often rejecting trades where the price moved against them, and accepting trades where the client was losing out. In 2015, this practice formed part of the case against Barclays in its settlement with the New York Department of Financial Services (see box: How asymmetrical trade rejections cost Barclays).

Added up across a bank’s trades, the asymmetrical approach could be a significant source of revenue, claims the global head of one bank’s forex business.

“Some banks have been doing this for years and years because it was profitable for these institutions. If you continue to stream and price huge forex spot tickets, and you continuously asymmetrically approach pricing to your clients based on whether the market moved in your favour or against you – relative to the price provided to the client – then you have some potential revenue associated with the last look,” he says.

The final version of the forex code did not address the issue of symmetry in trade acceptance and rejection, except to encourage transparency throughout the process. Bank disclosures show divergent approaches – and some complexity.

Nine banks, including Barclays, JP Morgan and Nomura, say they apply last-look price checks symmetrically.

Deutsche Bank operates an asymmetrical system by default, meaning a trade request will be rejected when the price moves against the bank – but not if it moves in the bank’s favour, up to an unspecified threshold.

In a disclosure that was updated on March 1, Deutsche Bank says this allows it “to provide customers with a deeper, more consistent liquidity offering, at tighter pricing and higher fill rates than it otherwise could” but warns the practice may result in a lower acceptance rate for trades “where the price moves against Deutsche Bank during the period of delay than where the price moves in its favour”.

If customers want symmetrical treatment, the disclosure states, they can opt out of the bank’s default position. Two other approaches are also available.

Societe Generale implements a similar asymmetrical approach “only after a number of successive occurrences where a difference above a threshold is observed between the requested price and the last updated price”.

Goldman Sachs says if the price moves in the client’s favour beyond a threshold it will be rejected. If it moves in the bank’s favour beyond a threshold it may be subject to a “price improvement” where the executing price is improved by the difference between the tolerance band and the final price, up to a maximum of 3 basis points.

For some clients, trading with their liquidity providers on an asymmetrical basis is acceptable – they buy the argument that it results in tighter spreads. Or so claims the head of electronic forex trading at one liquidity provider. “In the wholesale space, what you are trading off is the tightness of spread, the price of liquidity versus the reject rate, and all of the big electronic trading firms will have multiple price feeds with various combinations of parameters around that. It’s really the job of the salesperson to figure out which combination is right for which client,” he says.

Committing to the forex code

All of the banks featured in the disclosures table can probably argue they are in conformity with the global code. The questions that hang over the industry are how widely the principles will be adopted, and whether regulators and clients will push for further harmonisation.

There is currently no register of firms that have committed to the terms of the code, although the Global Foreign Exchange Committee – a body established to promote and update the code following its launch last year – has talked about setting one up. Several domestic organisations, such as the Australian Financial Markets Association, have launched their own registers, but they cannot compel institutions to become signatories.

End-clients in forex markets could play a part in promoting the code by requiring their counterparties to adhere. Some are checking, at least.

[The code] has to become embedded in best practice…. There is always that threat in the background that otherwise we will see the foreign exchange markets regulated with a capital ‘R’ – and that will be a lot harder for everybody

Jeremy Armitage, State Street Global Markets

Auna Dunlevy, head of liquidity and investments at the UK’s Royal Mail, says all the company’s relationship banks have signed up to the code. But the risk of being ‘last looked’ by a liquidity provider is not too much of a concern for Dunlevy.

“Very occasionally in the past there has been a situation where a price is withdrawn or something after you thought it had been done. It’s just a little irritating really. Like everyone, we want to trade at a good price but as we are doing it for hedging purposes and not profit we don’t trade as aggressively as that, so maybe our drivers are a little bit different,” she says.

A senior treasury adviser at another large corporate agrees, suggesting the code needs “time to spread” and as such it is too early for end-users to be “sanctioning” relationship banks.

Jeremy Armitage, global head of e-forex at State Street Global Markets, suggests that as regulators cannot force institutions to sign up, clients should be demanding compliance with the code, adding that professional bodies such as the Association of Corporate Treasurers also have a role to play in encouraging sign-up among members. He argues that if clients have four or five liquidity providers and can see they are being rejected 20% of the time when the rate has moved in their favour, they will simply stop using the bank.

“It has to become embedded in the best practice of user communities. And there is always that threat in the background that otherwise we will see the foreign exchange markets regulated with a capital ‘R’ – and that will be a lot harder for everybody,” says Armitage.

How asymmetrical trade rejections cost Barclays

In 2015, Barclays was handed a $150 million fine by US state regulator, the New York Department of Financial Services.

The bank reached a settlement with the regulator after it was found to be using last look to automatically reject foreign exchange spot trades that would be unprofitable for the bank, using it as a ‘general filter’ rather than a defensive mechanism.

The consent order said Barclays “failed to properly use last look due to the failure of systems and controls”. It described the bank as using last-look functions and rejections “broadly and indiscriminately, without first verifying if latency or arbitrage was involved”. When questioned on its practices by customers, information provided by the sales team was “insufficient and/or incomplete” and often staff themselves were unclear as to the operation of the bank’s systems.

Following the settlement, Barclays fired its then-head of automated flow trading for electronic fixed-income, currencies and commodities, David Fotheringhame. In its statement on the investigation, referring to Fotheringhame, the New York Department of Financial Services ordered the bank to “take all necessary steps to terminate this individual, who played a role in the misconduct discussed in this consent order”.

Fotheringhame has now taken the bank to an employment tribunal in London alleging unfair dismissal, accusing Barclays of running a “sham” investigation and using him as a “scapegoat”. He alleges the ability for the bank to dismiss unprofitable trades was inherent in the system and not administered at his discretion.

“To a large extent, I don’t have to do anything to last look to make it strict to high-toxicity clients,” he said in a January tribunal hearing, as reported by Bloomberg. He added that 97% of rejected US client trades were with hedge funds or brokers, suggesting the bank was not targeting ordinary corporate customers.

Pre-hedging: disclosures still patchy

In October 2017, former HSBC currency trader Mark Johnson was found guilty of fraud for front-running a $3.5 billion client order. He is the first individual to be tried as part of global currency manipulation investigations and is currently awaiting his sentence. It is in light of this judgement that some say banks are reviewing their pre-hedging policies, rather than being prompted by the publication of the global code.

“I think what you are seeing in these answers is considerable concern about deciding, not in their own mind, where the line is between pre-hedging and front-running, but where it is in the mind of people like the Department of Justice and the Serious Fraud Office. That’s why you are seeing different answers,” says the chair of one industry body.

Under the code, market-makers are permitted to pre-hedge trades, and therefore not assume the associated risk, when acting as a principal in a transaction, but are told this should be done “fairly and with transparency”. During the last-look period that is a feature of electronic trading, dealers are not allowed to pre-hedge unless acting as an agent, when the client trade and its offsetting transaction essentially occur as a package.

Most of the major banks say they comply with the code’s bar on pre-hedging in the last-look window. But five do not disclose their stance.

Some disclose that they may pre-hedge at other times. BNP Paribas, for example, says it does not engage in pre-hedging activities when trading electronically but may pre-hedge when voice trading or face to face, unless instructed otherwise by the client.

Deutsche Bank states it may hedge itself “prior to… or at the same time as executing a transaction with a customer”.

In a December 2016 disclosure, Morgan Stanley said the bank did engage in pre-hedging activities, but a revised document issued in June 2017 – just after the publication of the global code – explicitly rules out the practice.

The code’s key aim is improved communication, argues James Kemp, head of the Global Financial Markets Association’s global forex division. “It allows for different business models; it is not prescriptive. What it says is: ‘Let’s make sure that the relationship and communication between you and your client is clear about the basis on which you are transacting.’ That is what the whole code comes down to – a better dialogue about the basis on which you are transacting,” he says.

One of the code’s unresolved issues is whether and how to accommodate back-to-back trading that is common among smaller banks. This approach to liquidity provision might see a bank quoting a price but only accepting a trade if it is able to cover it within the last-look window.

“Typically the bank will show liquidity to a small bank that doesn’t have a trading team, and that small bank is then showing that liquidity to one of their clients. Technically, they are pre-hedging in the last-look window – which the code has banned – but they are doing it for legitimate reasons,” said one bank’s co-head of foreign exchange.

One global forex head argues a home needs to be found for this kind of trading within the code “otherwise there’s a massive part of the market that pre-hedges in the last-look window technically, including a third of the Japanese retail aggregators, as well as the Latin American and European retail banks. It is happening all the time.”

Correction, March 5, 2018: This article was updated to show that Deutsche Bank does not pre-hedge trades during the last-look window.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Markets

LCH expects to boost deliverable FX clearing with new adds

Onboarding of dealers and link-up with CLS could swell interbank deliverable FX clearing volumes

US block size changes reveal trillions in swaps trading

Fears of information leakage force some large buy-side users to adjust execution strategy

Trump’s tariff threats fuel corporate FX hedging revamp

Treasurers mull options and longer-dated hedges in face of mixed signals on extent and timing of measures

Pension funds’ appetite for long-dated gilts ‘temporary’

Gilt selloff spurs opportunistic buying but the trend is short-lived, say market participants

Why did UK keep the pension fund clearing exemption?

Liquidity concerns, desire for higher returns and clearing capacity all possible reasons for going its own way

How UBS sold off non-core equity assets at lightning speed

More than 40 auctions have been completed since Credit Suisse acquisition, with a little help from a T-Rex

‘Street Fighter’ Sef RTX grows in interdealer swaps market

Focus on functionality and fees helped volumes on start-up venue from Cawley and Jonns jump fivefold last year

Isda to finalise drafting updated FX definitions this year

New definitions on disruption events and fallbacks are core focus