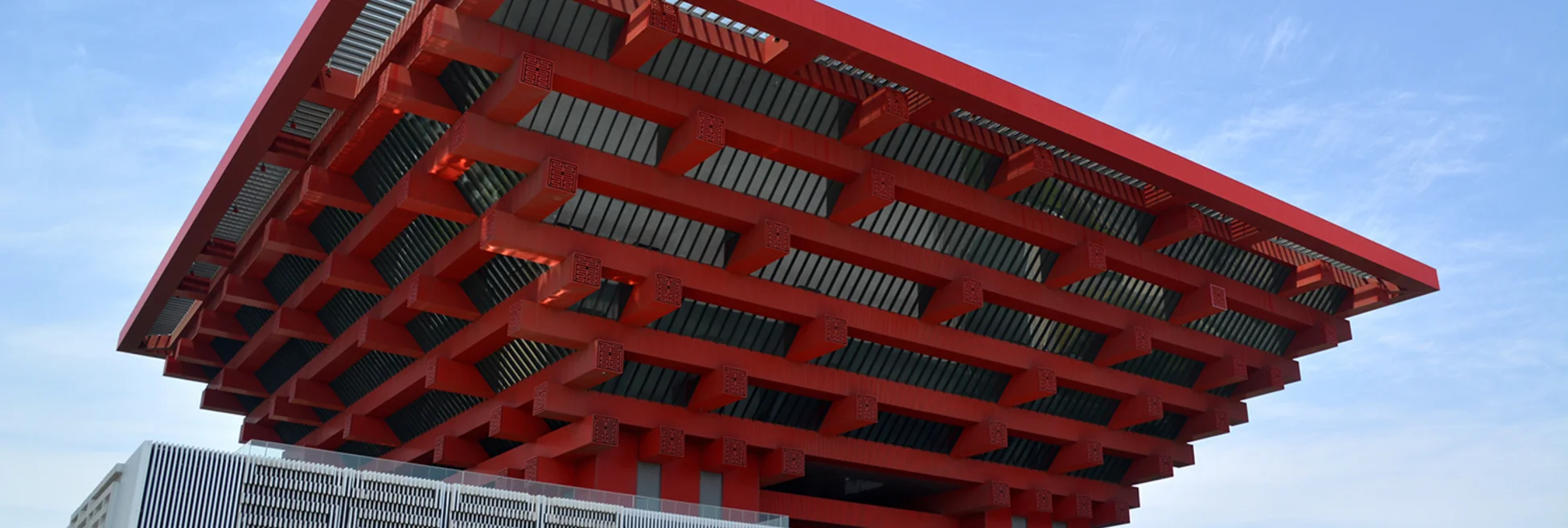

Global banks eye China’s structured products surge

Following a government crackdown on local products, foreign banks look to open joint ventures onshore

For investment banks eyeing a move into China’s glinting wealth management market, the stars seem to have lined up nicely.

A confluence of factors has led to an explosion in structured products, derivatives-linked investments sold by banks, in the first half of this year. China clamped down on traditional wealth management products, a trillion-dollar market hawking products that carried, if little else, an assumed guarantee against loss. Structured products, which can still offer some form of

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Markets

European investors ramp up FX hedging as ‘dollar smile’ fades

Analysts at one bank expect average hedge ratios to jump from 39% to 70% within six months

CLO market shakes off ETF outflows

Despite record redemptions, exchange mechanics and relatively small volumes cushioned impact

Pension funds hesitate over BoE’s buy-side repo facility

Reduced leveraged and documentation ‘faff’ curb appetite for central bank’s gilt liquidity lifeline

Wells Fargo’s FX strategy wins over buy-side clients

Counterparty Radar: Life insurers looked west for liquidity after November’s US presidential election

How BrokerTec, MarketAxess fared during Treasury rout

Electronic bond trading platforms see spike in volumes and small growth in market share, Risk.net analysis shows

Tariff volatility pushes banks to tighten close-outs

Lawyers say dealers are looking to update playbooks for terminating derivatives trades

Dodging a steamroller: how the basis trade survived the tariff tantrum

Higher margins, rising yields and stable repo funding helped avert another disruptive blow-up

SG’s Ungari swaps research for structuring in new QIS role

Veteran researcher and strategist ‘putting things into action’ with new remit