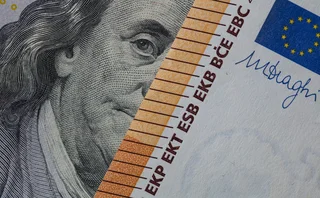

Corporates eye cross-currency swaps as Euribor sinks

The European Central Bank cut its benchmark interest rate to 0.05% in September 2014, tempting some corporates to swap their debt into euros and cut their debt service costs. But some see hidden dangers

Since the current period of low interest rates began, much of the discussion has centred on the difficulties the buy side faces in generating yield for investors. For corporate borrowers, though, it creates the potential for windfall savings in their debt service costs.

Not only can they finance themselves at historically low levels generally, but a recent cheapening of cross-currency swaps by up to 30% has enabled some to synthetically convert their debt into euros to take advantage of ultra

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Markets

Repo and FX markets buck year-end crunch fears

Price spike concerns ease as September’s surprise SOFR jump led to early preparations for bank window dressing

US senators press CFTC on Japan swap clearing

Boozman and Hagerty urge action on yen swap clearing access to JSCC in letter to US regulator

Traders dredge 0DTE data for intraday gamma insights

Firms such as UBS, BofA and OptionMetrics are investing in continuous net options position monitoring

Cross-currency futures could ease bilateral burden – CME

Quarterly €STR-vs-SOFR contract could be used by Stir desks to manage currency basis risk

‘It’s not EU’: Do government bond spreads spell eurozone break-up?

Divergence between EGB yields is in the EU’s make-up; only a shared risk architecture can reunite them

Long gamma puts brakes on post-election US stock rally

Call selling by ETFs helped fuel largest net gamma positioning among dealers since July

Credit risk transfer, with a derivatives twist

Dealers angle to revive market that enables them to offload counterparty exposures, freeing up capital

Consortium-backed FMX eyes push for FX unit

Formerly Fenics FX, the venue has seen growth from dealers and non-banks using its pegged order types and dark pool liquidity