Estimating the impact of US energy efficiency programmes

Increased interest in energy efficiency and demand response programmes in the US power markets has led to the birth of the negawatt – a tradable resource now gaining prominence in the industry. But estimating the impact of these programmes is not easy, as Elisa Wood discovers

Many US states are now mandating deep cuts in power use through energy efficiency programmes. However, for suppliers and utilities, working out the impact these programmes will have on their business models is proving extremely difficult.

Twenty-six US states, which account for 65% of the country’s electricity demand, now have energy efficiency resource portfolio standards with targets to reduce electricity demand over time. If achieved, the standards will take a 6% bite out of retail electricity sales nationwide by 2020, according to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE).

Because these, and other efficiency and demand reduction programmes, effectively increase supply, they have given birth to a new virtual resource – the negawatt – energy saved via energy efficiency measures. The negawatt is fast becoming a recognised tradable resource that can be used to bid in some of the US regional wholesale power markets head to head against power resources. The first to accept such bids was ISO New England in its forward capacity market. These negawatts have contributed to significant flattening of demand for capacity in New England.

Negawatts have not, however, created power markets that are any less complicated when it comes to navigating risk and reward, according to Daniel Allegretti, vice-president for energy policy with Maryland-based Constellation Energy, which operates in both wholesale and retail electric markets. In fact, they have added yet another wrinkle.

“As we’re seeing more demand response coming in flattening things out, we are also seeing more intermittent supply [such as wind and solar] come in. So I don’t think the markets are becoming less volatile from a trading perspective,” he says. “To understand it, to predict and see where to take a position, is becoming increasingly challenging,” he adds. “I wouldn’t say there is a magical algorithm.”

Indeed, it is ultimately the “grey matter” that must determine a supplier’s market position by taking in the many data points that influence demand, such as weather, rule changes, energy imports, regional transmission organisation information and new utility programmes, he says.

All these variables make trying to calculate the impact of energy efficiency and demand response extremely tricky. “The prevailing conventional wisdom is that energy efficiency will put downward pressure on demand and prices. I don’t think anyone argues with that. The $64,000 question is, of what magnitude,” says Martin Kushler, senior fellow at the ACEEE.

Overall demand appears set to rise despite energy efficiency programmes, due to a growing use of air conditioners and electronic devices. However, the rise is forecast at just 1% per year, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Retail electricity rates also appear to be levelling and may even fall, according to the EIA’s Short-Term Energy Outlook, published in March 2011. Household electricity prices showed no growth from 2009 and 2010, hovering around an average 11.58 cents/kWh, not an unexpected event during a period of slow economic activity and low natural gas prices. The same forecast shows electricity prices rising by 1% in 2011 and 0.5% in 2012.

But over the long term, prices may actually fall. An early release of EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2011 projects that real average delivered electricity prices will drop to as low as 8.9 cents/kWh in 2016 (see figure 1).

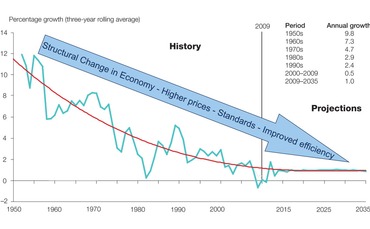

Figure 1. Rate of growth of electricity consumption

While projected electricity consumption grows by 30%, the rate of growth has slowed. Source: EIA, Annual Energy outlook 2011

EIA attributes the price drop to an ample supply of natural gas that will keep fuel prices low for power plants. But analysts say energy efficiency and demand response will play a role too. The tricky business is teasing out how much they will influence price compared with other significant variables such as fuel prices and the economy.

In addition, the programmes themselves are still something of a wild card for energy forecasters. Will they be successful, and by how much will they actually decrease electric demand? And what will it mean to wholesale power markets?

“My view is that many of the energy efficiency plans are relatively new; I just don’t think they have produced enough detailed data to make firm conclusions,” says Edward Hurley, a partner with law firm Foley & Lardner, who grappled with energy pricing issues as a member of the Illinois Commerce Commission for several years.

Still, it hasn’t stopped companies from trying. Synapse Energy Economics, for example, has taken on the tricky task of isolating what happens to wholesale electric energy and capacity prices when demand falls. The Cambridge, Massachusetts research and consulting firm refers to the phenomenon as Dripe, or Demand Reduction-Induced Price Effect. Synapse has looked at historical load and historical prices, and asked what happens to the price if load drops by a certain amount over the course of an hour. The analysis measures the change in slope. For example, if electric load drops by 1,000 MW, it is the slope on the supply curve that matters, and that curve changes constantly. Synapse has studied data in New England month to month, season to season and on-peak and off-peak to capture various changes in the supply curve.

Synapse calculated the avoided costs created by demand reduction – that is, how much more the six New England states would pay for power in the absense of their efficiency and demand response efforts. The avoided costs ranged from three tenths of a cent/MWh to 5 cents/MWh in 2009. The range is broad because it encompasses off-peak winter power prices and summer peak power prices – the high and low range of demand. The researchers concluded that while demand reduction may have little impact in any given hour, the affect on price accumulates over the 8,760 hours in a year.

Synapse cautions, however, against relying too heavily on the avoided cost numbers. Underscoring just how difficult it is to pinpoint energy efficiency’s effect on pricing, the researchers say the avoided costs would probably only be accurate for a few years because the drop in price will change market dynamics. Developers are likely to delay plans to build new power plants if prices drop. This in turn changes assumptions to the formula, according to the researchers.

“Say, for example, a firm was going to build a power plant in year three. Because the price has dropped, he decides to wait until year five or six to build the plant. Without that new plant in years three and four, energy prices get buoyed upwards a bit,” explains Doug Hurley, an associate with Synapse.

Hard to predict risk and reward

Why is demand reduction analysis important to power suppliers? Obviously, if electric demand falls, so does need for their product. But unexpected changes in demand also represent opportunities, particularly when they occur during peak periods, a time when prices are volatile.

It is important to note that the US is pursuing energy reduction through two kinds of programmes. One approach involves pure energy efficiency efforts, the other uses demand response. Energy efficiency programmes include home insulation, lighting controls, updated motors and chillers and other efforts that reduce the need for energy over time. Demand response, on the other hand, focuses only on those periods of time when energy use is high and prices spike – peak periods. Grid operators and utilities call upon large energy users to cut back on their energy use during these periods, often in return for financial incentives.

“They each have a different effect on the wholesale market,” says Constellation’s Allegretti. While energy efficiency creates a permanent reduction in energy use, demand response causes “a shifting and may not represent a large reduction in energy over a year”, he says. “But it reduces [price] volatility, so it leads to flattened rates. From a trading perspective, there is going to be a lot more impact to think through and analyse associated with demand response than simple energy efficiency, which is really just about the long-term forecast.”

The volatility of peak pricing creates risk and opportunity for power suppliers, because if they bet right on demand during those high price hours, they stand the chance of significant earnings; a wrong bet, though, sends them the other way. “Most of the risk, with respect to calculating what these energy efficiency programmes are doing, is on the peak,” says Mary Beth Gentleman, energy attorney and partner with Foley Hoag.

For example, under one scenario a supplier might choose to bid for a bilateral contract to supply standard offer power, which is an agreement to supply a utility’s load in a deregulated market no matter how much its demand fluctuates up or down. Before bidding, the supplier will carefully analyze anything that might affect utility peak demand, including the utility’s demand reduction programmes. A supplier who expects peak demand to drop more than the utility forecasts, will offer a low bid and win the contract. But if the bet is wrong, and utility peak is higher, then the supplier could end up shopping for the extra power in a pricey spot market.

Of course, demand reduction is only one element that the supplier must weigh in a risk analysis. “You have to put the energy efficiency performance uncertainty in the context of all these other market factors. What other resources will be available at peak? Will the demand resources continue to perform well? The bottom line is that energy efficiency is not nearly as significant as these other factors,” says Gentleman.

But as states increase their energy efficiency and demand response efforts, these resources will carry more weight in the market. “With any type of resource as it increases in its proportion in the overall supply mix, its risks and benefits become more pronounced,” she says.

If you can’t beat ’em…

In many ways, energy efficiency and demand response seem like the natural enemy of power suppliers, since they diminish need for a supplier’s product. But not all suppliers see it that way. When apple and banana sales fall, and pomegranate and avocado sales rise, some suppliers know to offer the new fruits,” says Stephen Cowell, chairman and chief executive officer of Conservation Services Group, a national energy services firm based in Massachusetts.

“There are brokers, traders and companies actively soliciting demand reduction and paying consumers for participating in those markets,” says Cowell.

Constellation, for example, decided that rather than fight the demand reduction market, it would join it by offering customers its own energy efficiency and demand response programmes.

“We certainly have not stopped being power providers, but we see what is happening in the marketplace,” says Allegretti. “We saw the enormous amount of political support [for efficiency and demand response programmes]. We saw it as something that was going to happen, not something that we should or could stop. We’ve always had the view that we should get in front, rather than sit back and be defensive.”

He adds that demand reduction programmes offer a great deal of ‘win-win’, allowing creation of negawatts that have no environmental impact and don’t need ‘to be built in anybody’s backyard’.

One question remains: are the demand reduction programmes achieving their intended goal of promoting least-cost supply first? Not yet, because the US is still in a nascent stage in achieving its energy efficiency goals, according to Paul Peterson, senior associate at Synapse Energy Economics. “To get to the absolute least cost you should be investing in all cost-effective energy efficiency, before you build a single power plant. We have barriers to implementation of energy efficiency. We have good business models about how to build a power plant, run it and make money. The business model for energy efficiency is not as developed,” he says.

But given the strong push by both state and federal policymakers for demand reduction, it seems the business model is coming, and with it some downward pressure on prices. While the US has retreated from efficiency in the past after prices dropped, market observers do not see that happening this time. “Energy efficiency is here to stay. Too much money, too much time and too much sweat has gone into these programmes for it to be otherwise,” says Foley & Lardner’s Hurley.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Environment-Renewables

European Parliament vote on carbon market reforms seen as bullish

Energy traders welcome reforms seen as shoring up ailing EU carbon market

Modelling the financial risks of wind generation with Weibull

The manner in which wind generation can affect the half-hourly APX price is discussed

EU TSOs need carrot to tackle congestion – EEX's Reitz

Power grid operators and capacity mechanisms seen as impeding cross-border trade

Q&A: Ercot's Doggett on wind power surge and EPA rules

Outgoing president and CEO discusses challenges posed by renewables in Texas

EU power traders rail against national interventions

Capacity and renewables schemes deterring investment, say panel participants

Weather house of the year: Munich Re Trading

Weather derivatives specialist wins praise for consistent, high-quality service

Emissions house of the year: CF Partners

Specialist knowledge of carbon market is crucial to company's success

Asian emissions markets seen as step in right direction

China and South Korea emissions schemes show promise, say industry groups