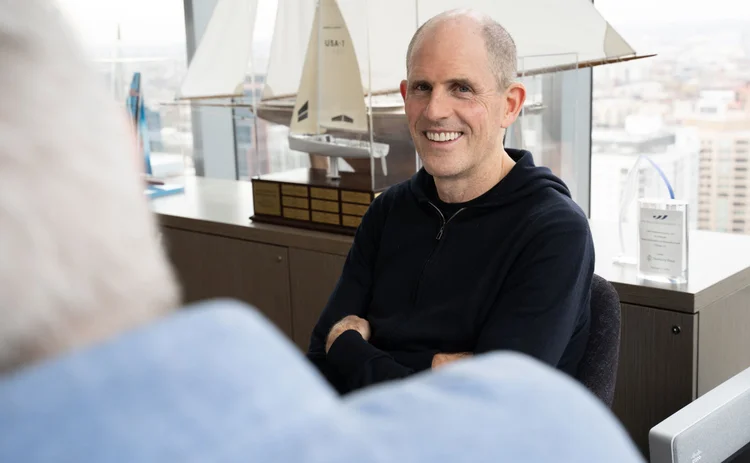

Lifetime achievement award: Don Wilson

Risk Awards 2025: DRW founder has created a firm in his own image – one that defies definition

Don Wilson was trading before he was a trader.

During his teenage years in Zurich, when Wilson walked along Bahnhofstrasse – the bustling home to many of the city’s banks – he had a habit of checking the foreign exchange rates each was advertising, looking for arbitrage opportunities. It was a purely theoretical exercise, he points out – the bid-offer spreads were too wide to take advantage of the discrepancies he spotted.

Later, as a junior member of the Zürcher Yacht Club, he completed his first sort-of trade when sailing around the Mediterranean. On this particular day – sometime in 1986, he estimates – there had been a big move in the Italian lira, which was known to Wilson when he set off from Genoa, but had not been reflected in the FX rates available when he reached Corsica. He borrowed some Swiss francs from the owner of the boat in order to – as he laughingly puts it – “pick up some arbitrage profits”.

Given that background, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Wilson found his way back across the Atlantic to study in Chicago, and then to the futures pits at the CME. It also won’t be a surprise that he was happy there.

“I loved it. I loved standing in the pit,” he says. “I grew up playing games at home, and there is a gaming element to it, but there’s also this math element, and just this really intense focus. And that’s a ton of fun.”

Wilson followed the fun from family card games to slow-moving Corsican currency trades, to the vibrancy and volume of the CME – and then beyond, to flickering screens and the faster-than-thought world of algorithmic trading.

Along the way, he accepted – more and less willingly – a stewardship role for the markets in which he was active. When needed, he sought to support and defend those markets; when asked, he was ready to help other participants.

He knew everything about market structure, about trading technology. He was strategic, he was thoughtful, he was direct. He was just a really, really impressive guy

Doug Cifu, Virtu Financial

Some of this is well-known: for example, Wilson’s years-long legal battle with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in a case that could have expanded the definition of market manipulation, and his firm’s participation in the auction of the huge Lehman Brothers futures positions at the CME.

Some of it is not. The successful auction of the Lehman books followed an earlier, flawed attempt. After participating in the initial auction, Wilson saw ways it could be improved. His suggestions were applied by the CME when it re-ran the high-stakes sale.

Nor has anyone talked about Wilson’s role in helping Nasdaq tighten up the default management process at its Swedish clearing house after the 2018 blow-up of power trader, Einar Aas.

“Don is like an engineer,” says Adena Friedman, president and CEO of Nasdaq. “He loves detail. He takes his role in the markets very seriously. We’ve reached out to him for advice on a number of occasions over the years, and he’s always happy to give his time.”

And when proprietary traders like Wilson’s DRW became the high-frequency trading villains of the Michael Lewis book, Flash Boys, it was Wilson who led the push to create an industry body that gave the sector its own voice.

Inevitably, many of Wilson’s interactions with other market participants are lower-key, but that doesn’t make them less meaningful for those who benefited. Here’s one example: when Vincent Viola left the New York Mercantile Exchange to launch Virtu Financial with Doug Cifu – a lawyer – Viola helped his co-founder acclimatise by introducing him to a raft of market bigwigs.

“We flew out to Chicago, saw Terry Duffy of CME fame, and then we went to see Donnie Wilson at his office. We spent, I remember, two hours with him, and I was floored, because he was an A-to-Z guy. He knew everything about market structure, about trading technology. He was strategic, he was thoughtful, he was direct. He was just a really, really impressive guy,” says Cifu.

He adds: “Vinny wanted me to meet him because his view of the world goes back to the pits where everybody was competing with each other, but you also kind of ran the exchange together. You would trade with each other all day, beat the shit out of each other, and then go have a beer and compare notes. I think Donnie sees it the same way.”

Sink or swim

Wilson’s early years were conventional enough. His mother was an occupational therapist, his father a lawyer with Libertarian sympathies. Wilson calls it a “pretty normal American life”. The family lived in a “nice neighbourhood” in Washington, DC, and he attended the local public school.

Then, at the age of 11, the family moved to Switzerland – initially, Lausanne, where Wilson’s father was taking a one-year MBA – before settling in Zurich.

As Wilson recalls, the cross-Atlantic leap was partly a reaction to Jimmy Carter’s presidency, the 1979 oil crisis, and round-the-block queues for petrol – “kind of a shitty time to live in the United States” – and partly motivated by his father’s interest in the Swiss system of government, with its emphasis on decentralisation and direct democracy.

Wilson’s life quickly became less conventional. He found it “super interesting”. To live in French-speaking Lausanne, the family learned the language prior to the move. Then, when they moved to Zurich, the 12-year-old Wilson had the summer to learn German prior to starting at the neighbourhood school – so his parents sent him to an intensive class for adults, which he travelled to from their home just outside the city.

“I’d take the train by myself to downtown Zurich and walk to the intensive adult German class and sit there all day, Monday through Friday. It was not your typical childhood thing,” says Wilson.

If this all sounds a bit sink-or-swim, it really was. Wilson was joining the Swiss school system in the fifth grade, when students were tested, then streamed by ability and sent to different types of schools, with very different prospects. Wilson calls it “the test that determines the rest of your life”.

As in Germany, the top tier of Swiss schools are known as ‘gymnasiums’. Despite only having months of German behind him – the source of much amusement for his Swiss-German speaking peers – Wilson made the grade.

“Somehow, I tested into the gymnasium. It was pretty remarkable, because even the math questions were all in German – they were word problems, which you had to answer using language, not just numbers. And then, of course, you have to write essays. But I got into the gymnasium and that was … I mean, it was an interesting experience.”

I was just on a mission. I wanted to get into the real world and start doing stuff

Don Wilson, DRW

Interesting, but not very enlightening. At the gymnasium, the emphasis on rote learning quickly began to grate, so he switched to a private American school, having already decided to go to college in the US. Then, when studying economics at the University of Chicago, Wilson spent orientation week taking “hours and hours” of tests, without taking the accompanying classes, racking up enough credits that he could think about completing the four-year course in three years instead.

When he reached that third year, however, one of the two classes he was excited about was cancelled, and the professor bailed out of the other, leaving it in the hands of a graduate student.

“I was like, ‘You know what? I’m not getting my money’s worth. I have enough credits. I’m going to graduate at the end of this quarter. I’m going to write my honors thesis now – in a quarter – which you’d normally spend a year doing, and I’m just going to be done.’ And so that’s what I did,” he says.

Formal education seems not to have done a lot for Wilson. He doesn’t say this, but a lot of the skills he would later need were self-taught. He’d already learned self-reliance and independence. He had a natural aptitude for maths. He had seen trading opportunities since his teens. And he taught himself to code on the family Macintosh: “I spent hours and hours, just teaching myself how to program and fiddling around with all sorts of stuff on the computer.”

Was he worried about missing things on his two-and-a-quarter-year sprint through college?

“I should have been, but I wasn’t. I was just on a mission. I wanted to get into the real world and start doing stuff,” he says. Wilson graduated in 1988.

The pits

His first chance to do stuff in the real world came with Letco, a small listed derivatives trading firm. Wilson – who had no contacts in the markets – had been “riding the elevators” of the CME and the Chicago Board of Trade, handing his resume to anyone he could find.

Letco initially had Wilson shadow each of the firm’s traders, learning what he could. Then, he was given $10,000 of capital to prove himself, trading listed FX and interest rate options.

By the second half of 1989, Letco had seen enough to take the training wheels off: Wilson was asked to choose a pit. Most of Letco’s traders were at the Chicago Board Options Exchange, trading equity options. Not for the first – or last – time, Wilson picked the less-travelled path.

“My thought was that it’s a lot more interesting to trade options on the short-term interest rate of the largest economy in the world than, you know, to trade options on IBM. It’s a more interesting product because the different parts of the interest rate curve behave differently as contracts roll down towards expiry. And so it becomes a more complicated set of derivatives to trade than index options or FX options,” he says.

It quickly got very interesting indeed, and not in a good way. Within weeks of entering the pit, now with a $100,000 account, there was a mini-crash that wiped out roughly a third of Wilson’s capital. It was a blow – Wilson says he was “sick to his stomach” – but, gradually, he managed to claw it back and then to grow.

The thing everybody observed was that I was trading in larger and larger size as my capital base grew

Don Wilson

This recovery owed everything to the work Wilson had been doing – in his own time – since joining Letco. Again, he’d been teaching himself. It started as soon as he had the chance to trade FX options.

“I’d go to the library at the University of Chicago and look up microfiche, collect economic data, and fiddle around with different stuff – build my own models,” he says.

This went up a gear when he entered the Eurodollar pit. Wilson says he learned some things from his colleagues – “thinking about risk, how to manage risk” – and was introduced to modelling concepts in books or videos. But applying those ideas was all his own work.

“I had one of those brick Macintoshes with the built-in screen. And I had a dot matrix printer, with a multi-coloured ribbon. And so, I set up a program that would run the option values, format them and print them. But it would take maybe an hour for the data to generate, and then it would take hours for the sheets to print out. I would get them going, and then put a pillow on top of the printer so I could get to sleep. In the morning, I’d collect them from the printer and take them down to work. Then, after work, I’d update the numbers and play around with it all. Eventually, I figured out some discrepancies in the vol surface that I thought were mispricings, and I started putting on positions to take advantage of them,” he says.

You could think of this as DRW 1.0 – a single strategy, based on one person’s analysis of Eurodollar options data, running on a single computer, with a modest pot of capital behind it. The mini-crash was a vicious welcome to the market, but over time, Wilson’s strategy began racking up gains, and his capital grew.

Going into 1990, Wilson estimates he had around $75,000 in his account. By the end of the year, he had made roughly $500,000.

He doesn’t say much about the strategy itself, except that he was short vega, long gamma and long wings. The source of the mispricing was “just a misunderstanding of the vol surface. It was pretty obvious to me. It wasn’t obvious to the rest of them, clearly”.

That may have been because no-one else had a DIY risk system and Wilson’s nose for sniffing out mispricings. It soon became apparent that Wilson was onto something – but nobody knew what.

“The thing everybody observed was that I was trading in larger and larger size as my capital base grew. Gradually I was able to move into better spots in the pit, I was able to hire some people. So, from that perspective, yes, it was noticeable,” he says.

The success continued. Two years later, Wilson had enough capital to start his own outfit, inspired by the example of firms like options specialist O’Connor & Associates and quant pioneer Cooper Neff.

Three out of four

You can split the 32-year life of DRW into two roughly-equal halves. In the first half, the firm became a big deal in listed derivatives markets, but had a pretty low public profile. Wilson may have been happy for it to stay that way – “There wasn’t a ton of value in us having a high profile,” he says – but from 2010 onwards, he had little choice in the matter.

Partly this was a result of the Lehman auction, the CFTC lawsuit, and the feeding frenzy that followed Flash Boys; and partly it was a natural result of the firm’s growing ambition, which saw it complete a string of acquisitions and venture outside of traditional prop-firm businesses.

Walt Lukken, now president and CEO of futures trade body FIA, was acting chair of the CFTC when he first met Wilson in 2007. The DRW founder had asked for an appointment with the market’s top futures regulator to discuss a rule-change to the way block trades were handled, which Wilson feared would make central limit order books less fair.

“He was very passionate, very principled in his views about how markets should work, and it made an impression on me,” says Lukken. “Here was this young individual with such strong views about Chicago School economics, and how these things should work, and I remember thinking that this gentleman would go on to do big things in the market.”

About 18 months later, their paths crossed again. Lukken was at the New York Fed during the Lehman Brothers weekend, “making sure the futures markets were preserved during the default and – sure enough – Don Wilson was part of that. It gave me comfort that Don was there in a time of crisis, helping ensure our markets were orderly,” Lukken adds.

The part played by Wilson and DRW was not widely known until April 2010, however, after a judge ruled that parts of the bankruptcy examiner’s report should be unsealed.

In commendably simple terms, the report laid out the facts and the sequence of events. On Friday, September 12, 2008, regulators told the CME that Lehman’s holding company would either be sold or in bankruptcy by the end of the weekend. The firm’s broker-dealer subsidiary – one of the largest clearing members at the CME with $4 billion in margin – was not expected to default at the same time, but would struggle to fund itself and would not survive for long. This triggered CME’s rule 975, allowing an ‘emergency financial committee’ to take a range of actions, including the liquidation or transfer of a member firm’s books.

On Saturday, the CME asked if it could share Lehman’s books with potential bidders; on Sunday, Lehman gave the green light.

Six potential bidders were approached, on the basis of their “capital, market concentration considerations and risk management expertise”. The firms were Barclays, Citadel, DRW, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley. All six were sent details of Lehman’s house positions on the Sunday, and five of them had submitted bids by the Monday. Those bids were not comparable, though – some firms bid for the entire Lehman portfolio, while others sought to buy exchange- or product-specific chunks of it. As a result, the auction did not create a proper market for the Lehman positions.

Wilson’s advice to the CME was simple: “I suggested they break it into energy, rates, equities, FX and another book for agricultural contracts and other commodities,” he recalls.

We ended up getting out of the first-order risk pretty efficiently – there was definitely some slippage, it definitely cost some money, but the market didn’t move too aggressively

Don Wilson

That is what they did. On Wednesday, the CME sought fresh bids from five of the original six – Morgan Stanley had not submitted an “acceptable” bid first time round and was excluded from the re-run, according to the examiner’s report – and required prices for each of the five portfolios.

It worked – all five portfolios were sold – but Wilson initially believed it had not worked in DRW’s favour.

On the Wednesday night, Wilson and his team met in the DRW offices, where they split the Lehman portfolios into different buckets of risk and priced each one. The proposed bids were challenged by Wilson – “I wanted to make sure they were charging enough, but not charging too much, and so we’d go back and forth on each of them” – and nobody got much sleep with a 7am deadline to hit.

DRW sent its bids in, and continued to run live market data through the various books, so the firm could see how the P&L was changing. The minutes ticked by. An hour passed.

“I sat there and waited. Eventually, by about 8.30, I came to the conclusion that other people must have bid more aggressively – and I was OK with that. I felt like we’d bid appropriately, I didn’t think we were overcharging. And then my phone rings,” says Wilson.

It was Kim Taylor – then head of the CME’s clearing house – and it was going to be a short call.

“She said, ‘Are you still there in the fixed income portfolio?’ And I looked at the screen, made sure the P&L was kind of ticking along in the same place, and said ‘Yeah’. She said ‘You’re done’ and hung up. That was it. I walked out of my office and yelled into our upstairs trading floor: ‘You’re all filled on the fixed income risk.’ And every single desk knew exactly what risk they owned at that point. And it was just beautiful – all the screens lit up, tons of volume going in as we started hedging out the key parts of the portfolio that we felt we needed to act on,” he says.

Wilson received two further calls from Taylor, each following the same pattern – first, making sure DRW was still happy with its bid, and then confirming the trade. In addition to Lehman’s house rates book, DRW landed the FX and the non-energy commodities positions.

The firm missed out on the energy book – won by Barclays – and the equities positions, which went to Goldman. The former still rankles. Wilson says DRW was in the process of switching from one clearing broker to another. The existing clearing member didn’t want DRW to bid – Wilson says this was due to “concentration issues” – and the new member wasn’t ready.

“We couldn’t bid on it, so we were super bummed out,” he recalls.

In all, DRW won three of the four books on which it bid – and those trades worked out well.

“It was good for us,” Wilson says. “We ended up getting out of the first-order risk pretty efficiently – there was definitely some slippage, it definitely cost some money, but the market didn’t move too aggressively. And a lot of the open interest just went into the big soup that was our position. We just ended up warehousing it.”

It was DRW’s first bow on the global stage, and the firm used the attention. After the release of the examiner’s report, which also revealed a total loss of $1.2 billion to Lehman as a result of the auction, details were splashed across outlets from the New York Post to the Financial Times. In the FT article, DRW was the only auction participant to provide a statement, noting that it was proud to “assist the CME when it determined that an emergency auction was necessary to assure the stability and continuity of the markets”.

Wilson says the firm put its head above the parapet to make a point – that if “something blows up”, then people should not conclude the right response is to “just call the banks. Because obviously, in this case, that wouldn’t have been a good outcome”.

“You won big”

In mid-2010, the chain of events began that would eventually lead to the CFTC accusing DRW of market manipulation, and potentially barring Wilson from the markets it regulated.

When the agency started asking questions in 2013, Wilson’s hope was that it rested on a misunderstanding and could be cleared up with a conversation. A meeting was organised with the CFTC’s head of enforcement. It did not go well.

“He said, ‘How is this any different from Libor manipulation?’ And I’m like, ‘Well, how is it similar to Libor manipulation?’. It was diametrically opposed. We had not done anything improper – quite the opposite. We had provided liquidity and uncovered a mispricing. But that discussion made it very clear that the lawyers didn’t understand, or didn’t want to understand, what was happening,” says Wilson.

A second conclusion followed hot on the heels of that first one: “We should never settle. We should litigate to the bitter end, because if what we did wasn’t allowed, then trading was not allowed,” he says.

So, what had the firm done, exactly? The story begins amid the unfurling wave of swaps market regulation that followed the subprime crisis – much of it seeking to import concepts and structures from the listed markets Wilson grew up in.

We had not done anything improper – quite the opposite. We had provided liquidity and uncovered a mispricing

Don Wilson

Wilson’s attention was drawn to a new ‘swap future’ contract launched by Nasdaq-backed start-up, International Derivatives Clearing Group. The argument was that over-the-counter market participants would start migrating to listed alternatives as mandatory clearing rules – and a relatively heavier margin burden – took hold in the OTC market.

The IDCG futures, dubbed ‘IDEX’, were promoted as “economically equivalent” to a corresponding OTC interest rate swap. In 2009, IDCG’s chief exec told Risk.net the contracts were “completely fungible with what is traded in the OTC marketplace”.

To a point, that was true. Like an OTC interest rate swap, IDCG’s swap futures brought together a payer of fixed rates with a payer of floating rates – respectively, the ‘long’ and ‘short’ sides of the contract. Like an OTC swap (of the time) Libor was the floating-rate benchmark. And, as in the OTC market, parties could negotiate their trades bilaterally.

But there were important differences. Those bilateral trades had to be loaded into IDCG’s clearing house, which calculated a daily settlement price – used to collect variation margin from whichever side was out of the money. As interest rates rose, a participant with a long IDEX position would receive variation margin, which could generally be reinvested at a better rate than the rates available to IDEX shorts, who would receive margin as rates were falling.

This difference between interest rate products with daily margin and those without gives rise to a so-called convexity bias. This effect had previously reared its head in other instruments, including the Eurodollar market, and in the clearing of OTC interest rate swaps, where it was offset by the introduction of a compensatory payment – price alignment interest, or PAI – from the margin receiver to the margin payer. But PAI was missing from the design of the IDCG contract, meaning it was not ‘fungible’ with the uncleared OTC trades it claimed to replicate.

Wilson spotted the missing component, then tasked a team of DRW quants and traders with exploring it further. Their conclusion was that IDEX contracts were significantly mispriced. By August 2010, the firm started trading the contract – always taking the long side, and offering to pay more than the corresponding OTC swap rate, but far less than its own estimates of the contract’s fair value. For market participants who had not cottoned on to the convexity issue, this looked like a great trade and, by the end of September, DRW had built a position of more than $300 million in notional, the bulk of it coming via a $175 million trade with Jefferies, and a $150 million trade with MF Global.

You won big. We lost big

Jefferies CEO email to Wilson

In the months that followed, DRW continued quoting – at an increasingly attractive premium to the corresponding OTC swaps – and concentrated its bids within the 15-minute daily window that helped determine the IDEX settlement price. This brought the market closer to what DRW saw as fair value. It also forced Jefferies and MF Global to stump up more margin.

If other parties had been attracted to the IDEX market, this could have become a wildly lucrative strategy for Wilson and DRW, but the market failed to take off and – in mid-2011 – came to a swift and messy conclusion.

First, IDCG asked DRW to explain its bids, at which point DRW pointed out the PAI omission and shared its own valuation formula that found a discrepancy of around 18 basis points between the 10-year IDEX contract and corresponding OTC swaps. Second, Jefferies sought to persuade IDCG not to use DRW’s bids when calculating the IDEX settlement price. IDCG refused – noting that it was following the contract’s specifications – after which Jefferies complained to the CFTC. The agency’s clearing division invited responses from IDCG and DRW, before concluding there was “no basis” to take action.

By now, DRW’s counterparties were wise to the economic difference that the lack of PAI created in the IDEX contract, but also accepted they had no grounds to go after Wilson’s firm.

After placing thousands of bids in 2011, but generating no further interest in the trade, DRW gave up on its strategy in August 2011, a year after it launched. In a tacit admission that DRW had correctly modelled the contract, the open positions with MF Global and Jefferies were unwound “at or near” the settlement prices established by IDCG, allowing DRW to bank roughly $20 million. The Jefferies CEO emailed Wilson at the time, with a magnanimous summary of the episode: “You won big. We lost big.” At the end of the year, IDCG told the CFTC that it was delisting the contract.

No basis in law

The story could have ended here, as the intriguing tale of a doomed contract and the short-lived opportunity it created, but – two years after the CFTC’s clearing division concluded there was no need to act on the Jefferies complaint – the CFTC’s enforcement division filed its lawsuit.

The main exhibit of the complaint was DRW’s behaviour in the first half of 2011, when the firm submitted daily bids – at increasing prices – during the settlement window for the IDEX contract. In the press release that accompanied its lawsuit, the agency described this as “banging the close” – an attempt to yank the market to a false level by stuffing through large trades at the end of the session.

The judge – Richard Sullivan, a former assistant state attorney who honed his skills prosecuting murderous drugs kingpins – saw it differently. His 15,000-word verdict marshals voluminous evidence in dismissing the CFTC’s case, but a lot of it boils down to a simple conviction: DRW genuinely believed the contract was mispriced, genuinely wanted to trade at the bids it made, and Wilson started offering better prices “not to gouge his existing swap counterparties, but to attract new counterparties and consummate new transactions”. Yes – IDEX prices were moved by DRW’s bids, but that’s how markets work. There was nothing fake about any of it, so the market was not being manipulated.

The CFTC had hoped to convince the court that even if DRW’s bids were sincere, the fact that it knowingly moved the market would count as manipulation. Sullivan gave this short shrift – warning it would lower the bar to proving market manipulation, and could impede a lot of normal trading activity: “This theory, which taken to its logical conclusion would effectively bar market participants with open positions from ever making additional bids to pursue future transactions, finds no basis in law,” the verdict states.

If they could define market manipulation in that way, then they could sue anybody for any reason at any time

Don Wilson

A lot of Sullivan’s conclusions contrast the evidence Wilson and his team provided in advance – and backed up in testimony – with the “sloganeering” that marked the CFTC case. But Wilson did not enjoy his days in court.

“The judge was quite aggressive,” Wilson recalls. “When the CFTC cross-examined me, they were kind of afraid to ask me questions. And then the judge said, “Are you guys done?” They said they were. He said, “Well, I’ve got some questions”, and then put on a show of how you actually cross-examine somebody, and some of it was pretty scary. But then, when the CFTC was giving closing arguments, the judge started berating their lawyer. One of the other CFTC lawyers took over, and the judge started berating them as well. I thought it was pretty clear which way the judge was leaning.”

Wilson still had to wait two further years for the judgement to arrive – and so did the rest of the derivatives market, which had been watching the case with almost as much concern as Wilson himself.

“The CFTC was trying to expand the definition of market manipulation,” says Virtu’s Cifu. “Any other firm would have paid some stupid fine, knowing they did nothing wrong. But Donnie wasn’t going to settle, he wasn’t going to compromise. And I have such respect for that. He did the industry a huge service.”

Wilson was glad to move on, but he rejects the idea that the case – brought while the CFTC was under the chairmanship of Gary Gensler – was some kind of regulatory blunder.

“It wasn’t an aberration. It was Gary Gensler trying to expand the jurisdiction of the CFTC. If they could define market manipulation in that way, then they could sue anybody for any reason at any time,” he says.

DRW is now in the foothills of a fresh showdown with a Gensler-led regulator. On October 10, the US Securities and Exchange Commission charged the firm’s crypto-trading subsidiary, Cumberland DRW, with unregistered trading of tokens the SEC believes meet the definition of securities. DRW responded by saying it was “ready to defend itself again”.

Financial platypus

Like other proprietary traders, DRW became a matter of public – and political – debate after the publication of Flash Boys. The book painted an alarming picture of high-frequency sharks who were feasting on retail investors by spoofing and front-running their slower-moving trades.

In Wilson’s eyes, that picture was a caricature, and the scrutiny that followed was unfair.

“Front-running is illegal. What Lewis was describing was just moving information from point A to point B more efficiently than other people, and trading on that information,” he says.

Did anything good come from the publication of the book? “No,” he says.

Are proprietary traders better understood now than they were? Wilson concedes that they are, but points out that “lots of misinformation had to be dispelled, which was very damaging, and took a very long time”.

In Wilson’s view, other consequences are still playing out. Banks and brokers now try to match more of their customer orders against each other – internalising the flows – rather than sending them out to the public markets.

“If the narrative is “Hey – when you send your order to a lit exchange, it gets front-run”, then people will internalise those orders or send them to a dark pool. That just erodes the central limit order books and – as we’ve seen over time – the percentage of volume on lit exchanges has declined. Ultimately, I think that’s a sign of an unhealthy market,” he says.

I was in this position where I had the math skills, the programming skills, the trading and risk management skills all in one, and that’s pretty unusual for one person to have

Don Wilson

Some of DRW’s peers – Jane Street and Jump Trading to name two – have responded by attempting to follow these volumes off-exchange and stream bilateral prices to selected market participants. In some cases, banks use these prices to power their own agency-type business – taking the prop trader price, adding a small spread, and beaming it to their customers. If a client bites, then the bank has the slightly cheaper hedge on tap.

DRW does this “in some products, but not nearly as many as we could”, says Wilson.

This is a willing, if somewhat regretful, adaptation. “In general, for the overall marketplace, we think having more of the volume on lit exchanges is better. It’s healthier. But obviously, if counterparties want to trade a different way, that’s their decision, and we’re happy to transact however they want to trade,” he adds.

On-exchange strategies have also changed somewhat. In the pre-Flash Boys days, a lot of high-frequency trading was essentially about capturing bid-offer spread – for example, an algorithm might base its quotes in a given market on the price of the best- and cheapest-available hedge in another market, then execute the two legs nearly simultaneously in order to collect a small, almost-risk-free spread.

This kind of strategy – and variants of it – remains a staple of the prop shop toolkit, but DRW and other firms now place more emphasis on using data about the balance of orders and the depth of a given market to peer a little way into the future. This information can be used by market-making strategies to skew their prices one way or another – building up positions that are expected to gain in value, then exiting them in time to salt away some profit – or for more traditional momentum-type investing.

Put simply, early high-frequency strategies relied on a firm’s ability to execute two offsetting trades before the price of the second trade could react to the execution of the first. The newer ones rely on a firm’s ability to anticipate price changes in a single market.

Wilson refers to the latter group of strategies as “mid-frequency trading”, and he sees their rise as a response to the success of the high-frequency strategies, which generated more competition and made it harder to generate a predictable return.

“I think that’s right – mid-frequency trading has become more important as these instantaneous expected-value trades kind of got arbed out. The market has become more efficient. That’s just a natural evolution,” he says.

But Wilson also notes that DRW was never a big protagonist of super-fast, risk-free trading. The firm initially picked up where Wilson’s own trading at the CME left off, focusing on the volatility surface for Eurodollar options, and looking for mispricings.

Which begs the question: what kind of firm has DRW evolved into? At a glance, it seems contradictory, or inconsistent. On one hand, it’s a creature of the Clob – designed to provide liquidity in electronic, public markets. On the other, it has ventured away from exchanges into the world of bilateral trading. It runs some of its strategies over vanishingly short time horizons. But it will also comfortably digest Lehman-sized books, and take big, research-led calls in illiquid contracts like IDEX, where risks have to be warehoused for long periods.

In all, Wilson says roughly a quarter of the firm’s traders are in rates, and a quarter in commodities, with the balance spread across FX, equities, exchange-traded funds, and crypto, among other markets. The firm has roughly 100 desks globally, and revenue is diversified across them.

This unusually broad combination of assets and trading styles makes DRW a financial platypus – hard to assign to a particular phylum and class.

For Wilson, there’s nothing weird about it. What kind of firm is DRW? Well, it trades. It’s a trading firm – and one built in his image.

“I don’t think I was that nuanced about it,” he says, when asked if he knew how he wanted DRW to stand out from other prop traders, when launching the firm. “I was in this position where I had the math skills, the programming skills, the trading and risk management skills all in one, and that’s pretty unusual for one person to have. What I was really focused on was leveraging that combination of skills to provide liquidity in the market and identify opportunities for capturing expected value. That’s what it was all about. That was the focus of the organisation I wanted to build.”

That is the organisation he did build.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Awards

Clearing house of the year: LCH

Risk Awards 2025: LCH outshines rivals in its commitment to innovation and co-operation with clearing members

Best use of machine learning/AI: CompatibL

CompatibL’s groundbreaking use of LLMs for automated trade entry earned the Best use of machine learning/AI award at the 2025 Risk Markets Technology Awards, redefining speed and reliability in what-if analytics

Markets Technology Awards 2025 winners’ review

Vendors jockeying for position in this year’s MTAs, as banks and regulators take aim at counterparty blind spots

Equity derivatives house of the year: Bank of America

Risk Awards 2025: Bank gains plaudits – and profits – with enhanced product range, including new variants of short-vol structures and equity dispersion

Law firm of the year: Linklaters

Risk Awards 2025: Law firm’s work helped buttress markets for credit derivatives, clearing and digital assets

Derivatives house of the year: UBS

Risk Awards 2025: Mega-merger expected to add $1 billion to markets revenues, via 30 integration projects

Interest rate derivatives house of the year: JP Morgan

Risk Awards 2025: Steepener hedges and Spire novations helped clients navigate shifting rates regime

Currency derivatives house of the year: UBS

Risk Awards 2025: Access to wealth management client base helped Swiss bank to recycle volatility and provide accurate pricing for a range of FX structures