Banks look to spin money from their own data

Big banks are tiptoeing forward with datasets for sale despite a host of internal obstacles

Need to know

- Banks are proceeding with care in the business of selling proprietary data to buy-siders.

- Forays into selling data have been slowed by concerns over confidentiality, internal battles over its use and work to be done on cleaning data up.

- “In our conversations with banks, they tend to get trigger-shy because they don’t want to be perceived as revealing confidential information. There are so many internal frictions,” says Tammer Kamel, founder and chief of Quandl, a platform for alternative data.

- Another question is to whom banks can sell and whether they are barred from touting internal data to just a few favoured clients.

- Bank traders worry about buy-siders using the data to trade against them. Buy-side traders fret about front-running by bank desks that see the data first.

Mark Zuckerberg has faced firestorms over privacy and regulatory issues as well as on the subject of enriching Facebook on its users’ data. Could Wall Street handle its own suite of those problems any better?

It may one day have to. The world’s largest social media hangout drew a wall of vitriol when it became known that the data of 87 million of its users had been leaked. Wall Street, a fortress of calculation and polar opposite of the populist Facebook, is doing its level best to sidestep any such rancour with a soft entry into the world of selling its own data.

Very soft. Banks have been talking privately to asset managers about data sales, but are generally reluctant to confirm they have entered the business – or to deny it.

A big reason for the low-key entry has been the push-and-pull inside the banks over the new business: what data to sell, from what division, how to format it, how to avoid legal problems, and a curious one: will we end up competing against ourselves?

In May, it emerged that Goldman was in the early stages of identifying datasets generated internally that could be packaged and sold to fund managers; it is still navigating client concerns around confidentiality. State Street, a custodian bank, has said it has been providing data to clients for years as part of a broader strategy and is considering monetising some data in future.

But Goldman is hardly alone.

“All the investment banks are trying to sell their data,” Andrew Chin, chief risk officer and head of quantitative research at AllianceBernstein, says.

Besides Goldman’s fledgling effort, Barclays, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley and UBS and are all said to have held furtive talks with select asset management clients throughout the year on the prospect of selling internal or proprietary data.

Citigroup and Credit Suisse said they are not selling client data. Barclays and UBS declined to comment. JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley did not respond to requests for comment.

“All the bulge brackets are all in the early stages,” says a chief investment officer at a quantitative hedge fund, referring to the biggest multinational banks. The banks’ products still need a little work, he says. “There are data-quality issues with mapping that they need to improve on, and other technical issues we’re seeing in the data at this point,” he adds, noting that he himself is in the process of testing a couple of those products.

Banks have the potential to generate tens of millions, maybe even hundreds of millions, if they sell their gems

Tammer Kamel, Quandl

Even with products in their infancy, the effort is underway, under the radar. And as with most things digital, there is probably no turning back from what promises to be a tidy business.

“Banks have the potential to generate tens of millions, maybe even hundreds of millions, if they sell their gems,” says Tammer Kamel, founder and chief of Quandl, a platform for alternative data.

Mission creep

The banks’ forays into the world of alternative data have been slowed by an array of factors, most of them internal. A number of asset managers say they were approached by banks as far back as a year ago, and the banks’ struggles have been palpable even from the outside.

One chief risk officer at a billion-dollar fund manager, who requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the client relationship, says that both JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley had approached the fund to sell them data.

“JP Morgan engaged us and other buy-side clients to see what data we wanted from their broker-dealer,” he says. “They came back and said those datasets could be sold, but they haven’t got back to me.”

That was a year ago. He is guessing “they’ve had a lot of issues”.

Meanwhile, a small team from Morgan Stanley in charge of selling data also approached the fund manager with four of five pieces of data. But “they had to go to each team in the firm and beg for access to the data”, he says. “That’s not easy.”

The hold-ups include everything from confidentiality, internal fiefs reluctant to give up their numbers, to making the data ingestible. “That’s why we haven’t got too far down this road,” the risk officer says.

The issues banks need to sift through are many, and have no simple answer. But the biggest is the confidentiality of its clients, a landmine for pure online companies, let alone the discreet, money-padded world of Wall Street.

“In our conversations with banks, they tend to get trigger-shy because they don’t want to be perceived as revealing confidential information,” says Kamel. “There are so many internal frictions. Just to get through legal and compliance can be daunting as they need to protect customers.”

Robert Frey, chief of the FQS Capital Partners hedge fund, called it a “knotty ethical question”. When the banks release that data, “they are also releasing information that some of their own clients might consider proprietary or confidential”. The trading-patterns data has to be scraped of any identifying information, he adds.

But it is flow data that is most sought-after by asset managers – a look into the mechanics of price formation and the positions of the biggest actors in the market.

“Client portfolio content or client trading data is what the market would love to know,” says Jessica Stauth, managing director of portfolio management at the Quantopian hedge fund. “At a high level, the banks need to figure out how aggregated and anonymised the client holding and flow data needs to be before a client is comfortable with their data being part of dataset that’s being monetised.”

Chin at AllianceBernstein says that is exactly what the banks are working on.

In early talks with one investment bank, Alliance asked for forex and bond flows data broken down by hedge funds, long-only funds and corporate clients flows and positioning as a way to measure crowding. But the investment bank declined, begging off because it said it might be possible to guess the identity of a client based on trade size.

While this tale is reassuring, it might leave clients uneasy – they are being asked to trust the ethics of large banks. This area of data privacy is new – it is neither fully covered by existing client agreements nor even defined by regulation or law.

Getting behind the velvet rope

Besides figuring out which datasets to sell, banks are figuring out who they will sell the data to. The idea that the data should be available to any buyer seems to have occurred to no one.

At a European investment bank looking to get into the business, there have been difficult conversations within the compliance division on the possible legal fallout of making data available to select clients only, says a market-data manager there.

“Are you going to make the data to available to the Street? Are you going to make it available to all your clients? Only some? And what are the legal ramifications of that?” he says.

“There are compliance concerns in relation to Mifid II best-execution with supplying some specific datasets to a specific population because we have to treat clients in the same way,” he adds.

Ernest Chan, a managing member of QTS Capital Management, has a long list of datasets he would like. Besides order-flow data, there is allocation of client assets to different sectors or countries, frequency of trading or average holding periods, leverage or margin usage, duration and credit ratings of fixed-income holdings, client accounts’ profitability across different types of clients and client derivatives transactions summary data and positions exposure.

But QTS Capital is not trying to get any of that from any bank.

“No, we are not clients of any banks, and I believe they will first approach their own prime-broker clients first,” Chan says. “Since it is their data captured from their own clients, they are free to choose to sell that to whomever,” he says, adding that he’s not bothered by this.

The sale of coveted data to the richest clients may render Wall Street’s uneven playing field even more so. Already, banks favour behemoths over small fry in pricing trades, given the sheer volume of business at stake.

So why now?

The arrival of big institutions to the data-dive business has been a while coming. But asset managers have been panting over what advantage they might gain from the massive troves of the big banks.

The idea that quantitative analysis should influence, if not drive, investment has become a cliché on the buy side; asset managers are avid for new flavours of data beyond market-tracking and fundamental analysis – alternative data – in the search for trading signals.

Chin at AllianceBernstein says data on aggregate holdings and trade data across the bank’s client base would be very useful to get a sense of the views and inclinations of market participants.

“From our perspective, they know we want it because if we can get a little ahead of the competition, maybe we’ll make alpha,” he says.

All the banks are trying to commercialise their data because no one else has it. It’s a new revenue source

Andrew Chin, AB

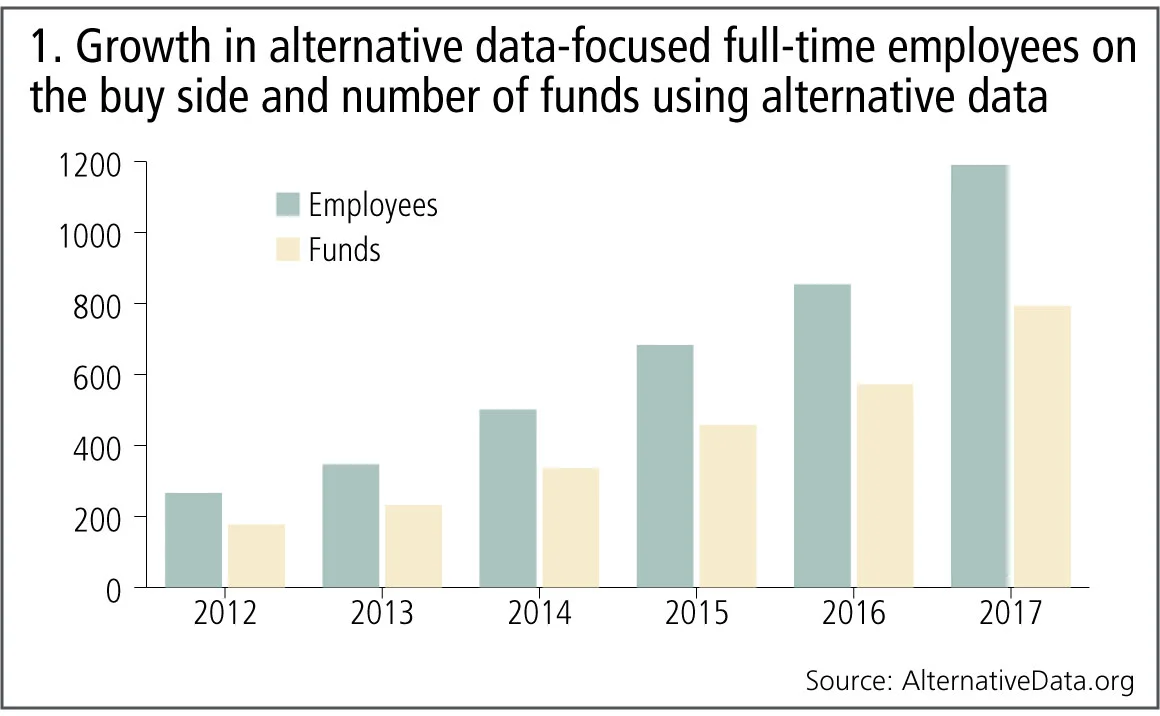

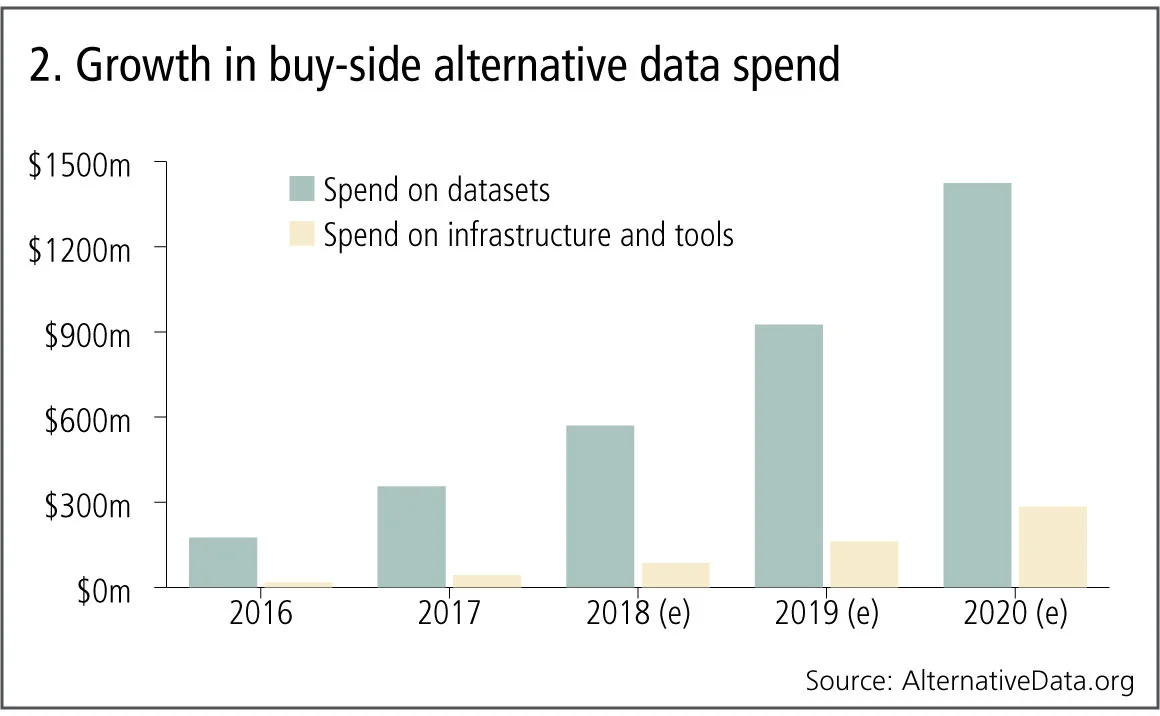

Total buy-side spending on alternative data is projected to reach $1.7 billion by 2020 from $656 million this year. The number of employees who work directly with it – data analysts, scientists and engineers – has quadrupled to 340 since 2012, according to AlternativeData.org, an organisation that tracks the business.

Quandl, a platform for alternative data, has maintained a partnership for the past few years with CLS Bank International, which settles foreign exchange transactions for banks, brokers, funds and corporations. CLS provides the Quandl platform with aggregated and anonymised flow and volume data in a form that offers customers a view of liquidity in the forex market. Kamel, chief of Quandl, says the bank flow data is one of the best sellers.

“There’s no doubt you do better if you trade in the know,” he says. He adds that two bits of “data gold” are flows data on assets they make markets for or deal in, and consumer insights from retail business. Several asset managers also cite flows data as the most valuable data from banks.

Derivatives are another area of interest. “For over-the-counter asset classes, the dealers actually produce the most valuable data in the marketplace in terms of their pricing information,” says Chris White, founder and chief of ViableMkts.

George Mussalli, chief investment officer of PanAgora Asset Management, says he is also interested in derivatives products such as volatility surfaces for options pricing and prices on esoteric over-the-counter securities created by bank options desks.

The banks, he says, have “been manually creating these surfaces every day for last 20 years, and now they are going through their history and the directory of data sitting there and trying to monetise it,” he says.

For the banks, the business is too promising to ignore. “All the banks are trying to commercialise their data because it’s proprietary and no one else has it,” says Chin. “Obviously it’s a new revenue source.”

And the banks may be looking to alternative data to recuperate lost revenues from proprietary trading, complex derivatives and physical commodities. Data could be a lucrative business line.

Although not an apples-to-apples comparison, revenues from the data businesses of the world’s biggest exchanges grew 9% to $5.9 billion in 2017, with data accounting for one-fifth of total exchange industry revenues, according to market research firm Burton-Taylor International Consulting.

The move to monetise the data is also part of an ongoing effort at investment banks to avoid giving away the intellectual property rights on their data to market-data distributors that sell products or create analytics using bank data, the market-data manager says.

Who’s on the other side?

A further source of contention is between those in the bank trying to sell the data and traders: their own and those of any house buying the data.

“The execution desks say, ‘If you make my trading data available to a limited scope of clients, the first thing they are going to do is arbitrage me.’ The sales people say, ‘We should give our clients what they require to make an informed decision because that will increase execution flow.’ But will they trade with you or against you? The question remains,” the market-data manager says.

This concern is on their minds of hedge funds, too. Yet another is, if a fund buys data, how do they know the bank selling it has not already flagged it to its own traders?

“As we get into this process with the banks, one thing we have to get comfortable with is that there is no delay in us getting it versus people in the bank,” says Mussalli at PanAgora.

“We haven’t gotten that far, as we’re still in the testing phase,” he adds. “But that’s a red flag for us.”

Editing by Joan O’Neill

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Asset management

Execs can game sentiment engines, but can they fool LLMs?

Quants are firing up large language models to cut through corporate blather

Pension schemes prep facilities to ‘repo’ fund units

Schroders, State Street and Cardano plan new way to shore up pension portfolios against repeat of 2022 gilt crisis

Fears of runaway risk on offshore reinsurance

Life insurers catch the eye of UK regulator for pension buyout financing trick

Hot topic: SEC climate disclosure rule divides industry

Proposal likely to flounder on First Amendment concerns, lawyers believe

‘Brace, brace’: quants say soft landing is unlikely

Investors should prepare for sticky inflation and volatile asset prices as central banks grapple with turning rates cycle

Trend following struggles to return to vogue

Macro outlook for trend appears to be favourable, but 2023’s performance flop gives would-be investors pause for thought

Start-up bond platform OpenYield prepares to launch

Start-up aims to give retail brokers the same electronic liquidity used by the professionals

Can machine learning help predict recessions? Not really

Artificial intelligence models stumble on noisy data and lack of interpretability